This is the last chance to see the UK’s largest ever exhibition of Alexander Calder (1898-1976) at Tate Modern, untill 3d of April.

Calder was one of the truly ground-breaking artists of the 20th century and, as a pioneer of kinetic sculpture, played an essential role in shaping the history of modernism. Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture brings together approximately 100 works to reveal how Calder turned sculpture from a static object into a continually changing work to be experienced in real time.

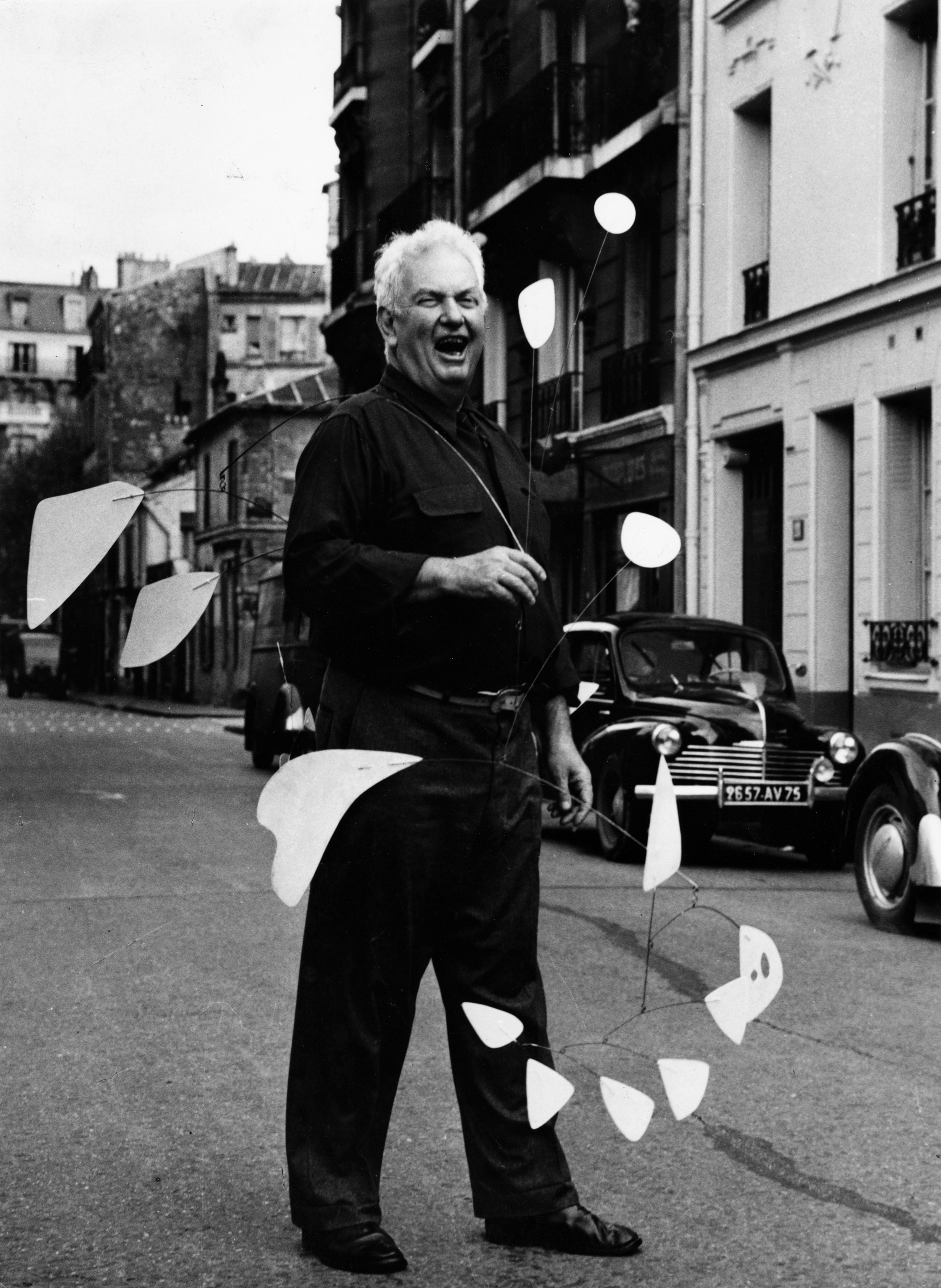

Alexander Calder with Snow Flurry I (courtesy Tate Modern)

What was the urge to organise this exhibition and what was the process of selection of the works?

It has been over 20 years since the last major exhibition of Alexander Calder at a public institution in the UK and over 50 years since a solo show of the artist’s work was last held at Tate. No previous Calder exhibition in the UK has explored how performance influenced the artist’s practice. Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture marks the first exhibition of the artist’s work to focus on performance as a major theme. Since its inception Tate Modern has provided a unique platform for performance practices and for artists to experiments and collaborate. It was felt that this was the right moment to present an iconic modernist artist and the development of an extraordinary practice that influenced and continues to inspire visual arts and performance on equal measures.

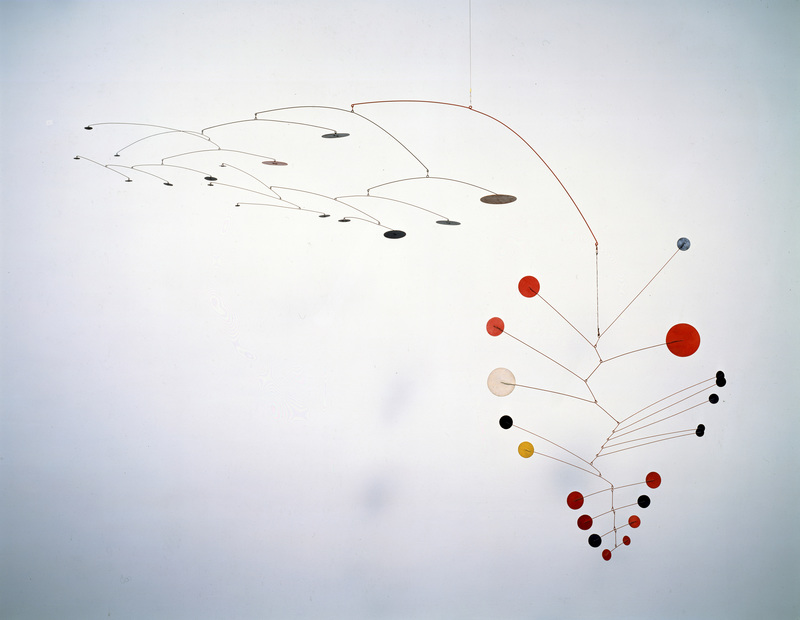

Gamma (courtesy Tate Modern)

What is the concept behind this exhibition?

The exhibition brings to the fore the radical nature of Calder’s thinking by exploring the notion of performance as a driving force in his renovation of sculptural language. Calder’s pioneering role was to have recognized that sculpture could move of its own accord and that the spectator no longer had to circumvent a static object. It was, of course, primarily his mobiles that made this insight actual and revolutionized the field, opening up the art work to the experience of time and concept of the fourth dimension, as well as to chance, contingency and performance. Calder conceived his sculptures as performers animated by air currents, mechanics or touch, so that through balance, motion and colour he could activate a ‘ballet without dancers’. The idea of movement and action are strong aspects of the show. Furthermore, composition through motion brought, theatricality and choreography are also concepts that are explored in the exhibition through a careful selection of sculpture and drawings.

Black Frame (courtesy Tate Modern)

There are many works at the exhibition, which gives direct references to the works of other artists like Miro, Arp, Leger and other modern artists. To which extent do you think they influenced each other, and how significant was Calder's vision in this circle.

Calder’s ability to move fluidly between concepts, ideas and art movements, made him a unique figure in art historical understanding. He was very close to most of the artists that were part of the avant-garde groups in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, forging strong relations with some of the key figures, such as Joan Miró, Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Piet Mondrian but also Fernand Léger, Edgard Varèse and Amédée Ozenfant among many other. That was a time and a context where the development of radical new concepts and the cross-fertilisation of artistic disciplines was as intense as it appears to be today. The rich links, connections and constant dialogue between artists and practitioners delineated a fertile ground for ideas to circulate. Calder’s influence was very strong, as he was constantly inventing new techniques and evolving the sculptural vocabulary, liberating sculpture from established traditions. His achievements on kinetic art, motion and movement not only influenced the circle of his artists-friends, but strongly resonates today with contemporary artists that are inspired by similar concerns and issues.

Blue Panel (courtesy Tate Modern)

When you look at some works that were inspired by circus, it brings you back to a childhood. And Calder with an ease transfers it into his works. How important was this playfulness for Calder?

Calder’s interest in the Circus and the development of the Cirque Calder, which is undoubtedly one of Calder’s best-known creations, is a celebration of sculptural movement, motion and performance. Calder was interested in the ways in which the bodies of acrobats function in space, the trajectories they describe in their various routines and the tension and suspense of an actual performance. The Circus exemplifies Calder’s ingenuity and virtuosity in creating objects that can function in equilibrium, in combination with each other, characterised by grace, delicacy and humour. His explorations of performance and live action through his miniature Circus not only brought him considerable renown in the avant-garde artistic sphere. They also established the conceptual basis for the evolution of his astonishing career, a career that transformed the route of art history through understanding the potentials and possibilities for sculpture when infused with elements of movement and aliveness.

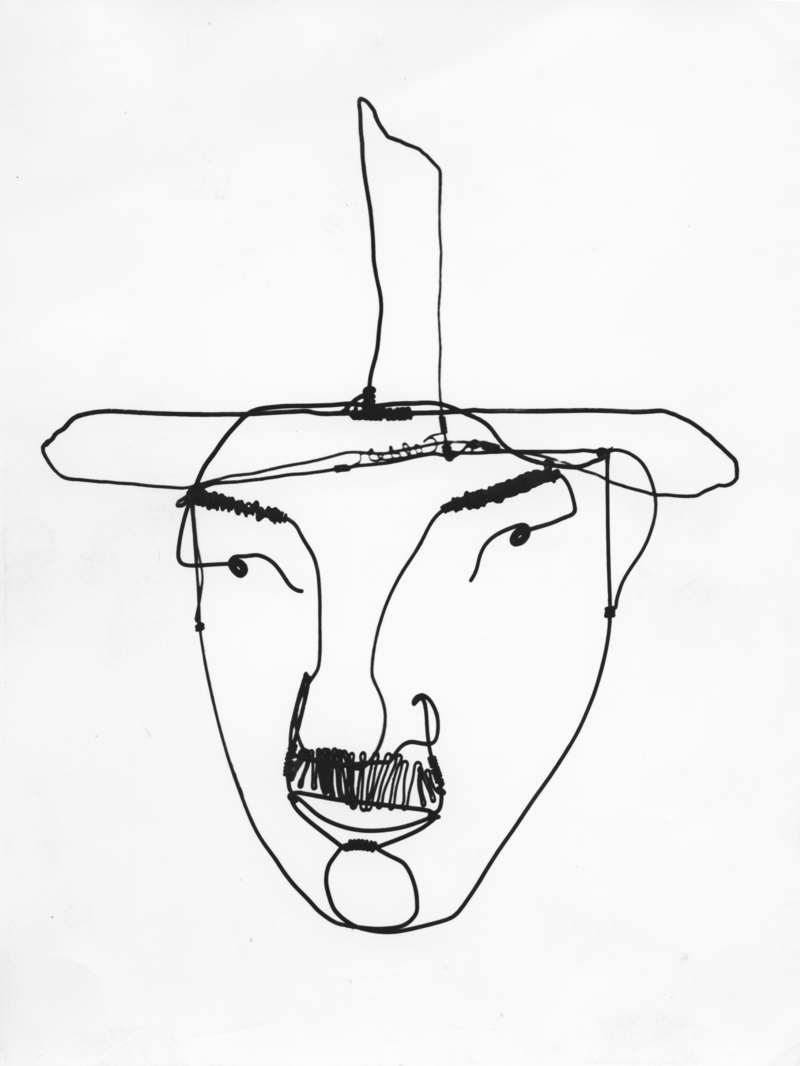

Fernand Leger (courtesy Tate Modern)

I think the title of the exhibition "Performing sculpture" is absolutely ideal, as his works are like actresses on the stage playing with the audience. What do you think about it? and what did you feel when installing the works?

Calder’s output and the ideas of movement and composition through motion offer a strong parallel with dance, choreography and theatre. One can certainly think of the mobiles as intrinsically theatrical objects. In addition, Calder’s practice was constantly concerned with infusing kinetic and elements of aliveness to inanimate objects. As I got to spend time with many of the works, trying to understand their movements and how they behave once installed, I was made aware of the mastery with which Calder has created them, infusing character and individuality into each one of his sculpture. Like dancers, they are all part of a continuous performance that never stops but always changes based on every presentation or space where they are being exhibited.

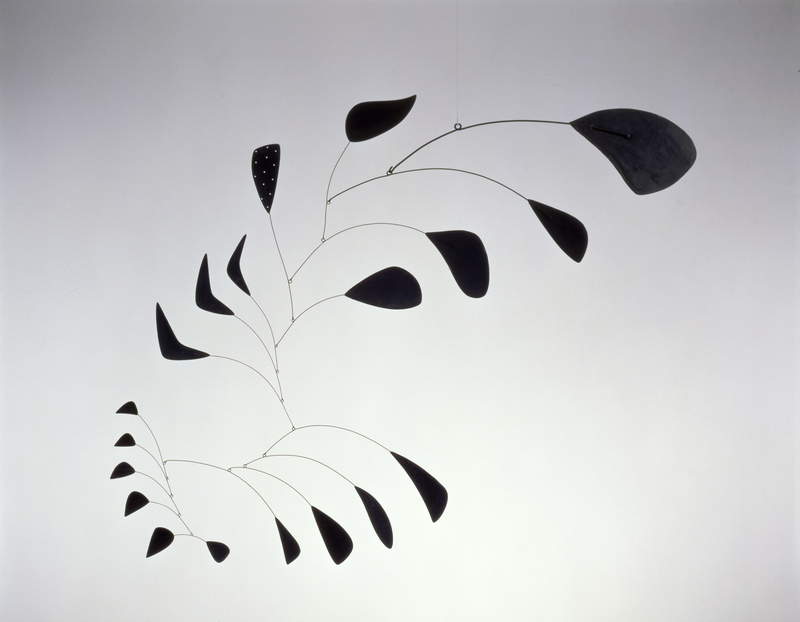

Vertical Foliage (courtesy Tate Modern)

The way the exhibition is organised and the impression that it makes is astonishing. What were the main curatorial issues?

The exhibition is titled ‘Performing Sculpture’ in order to capture the ways in which Calder’s work embodies the realization of an action. The main curatorial concerns were to reveal how Calder turned sculpture from a static object into a continually changing work to be experienced in real time. As with all Tate exhibitions, we wanted to address a fresh perspective on the artist’s practice, focusing on the notion of performance as a driving force in his work – an element that has been little explored up until now. Furthermore, our aim was to present a significant number of art works that have not been exhibited for years and which would allow Tate’s international audience to rethink the practice of Alexander Calder, one of the most loved and appreciated twentieth century artists.

During the exhibition tour, you've showed one mobile that Calder kept in his bedroom, and it looks a bit different from all other ones. Why do you think this particular work was special to him?

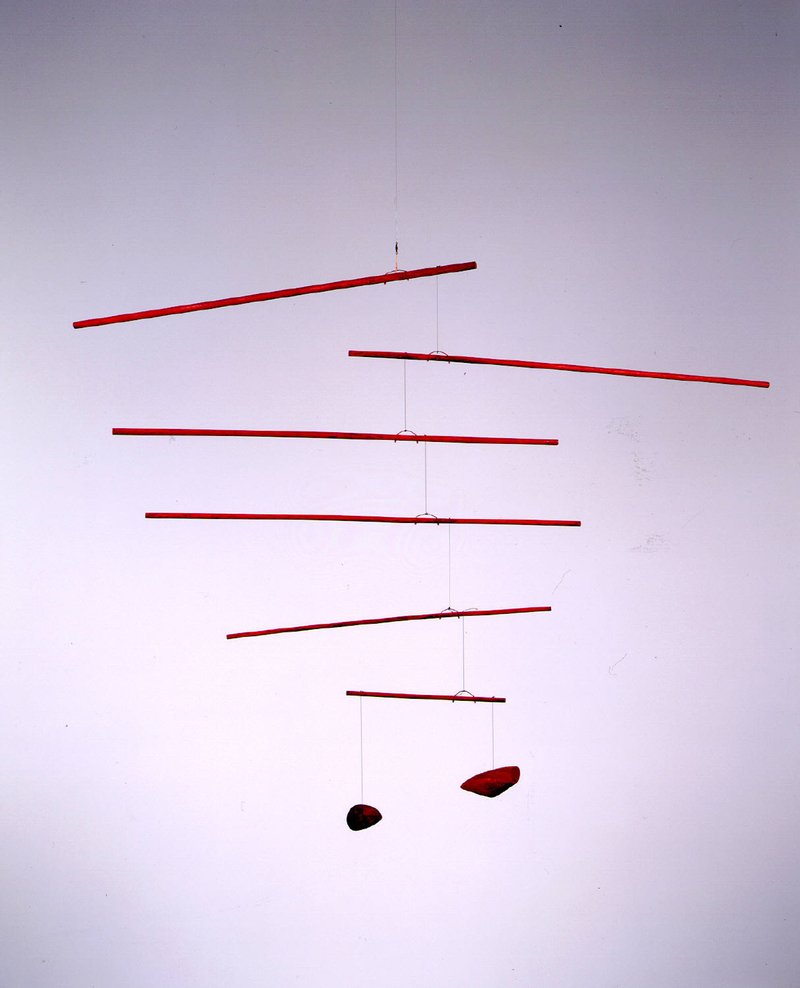

Red Sticks (c. 1942) is indeed very different from other mobiles. It is the only sculpture that mainly consists of horizontal elements. It is very difficult to even find horizontal lines in Calder’s mobiles as a horizontal line can have an impact on the kinetic potentials of the art work. I believe Calder liked to have this mobile in his bedroom because of the serene and delicate rotation it describes. Also, the shadow, which is unique among his mobiles and appears as being completely different from the work itself, must have fascinated him. His house and studio in Roxbury, Connecticut were bathed in natural light and I am certain he enjoyed seeing the sculpture and its shadow in all their complexity and individuality every day.

What is your favourite work from the exhibition?

There are many works in the exhibition, which I absolutely admire. However, my best highlight is the Black Widow c. 1948, one of Calder’s largest mobiles which is being shown outside of its home in Brazil for the first time in its history. Black Widow is a monumental sculpture measuring 3.5 metres that has hung in the lobby of the Instituto dos Arquitetos do Brasil (IAB) since it was gifted to the institution by Calder in 1948. The exhibition at Tate Modern offered a rare opportunity for Black Widow to not only be shown in the UK for the first time, but alongside other works that haven’t been seen for a long period of time.

Red Sticks (courtesy Tate Modern)

I'm sure, you did an enormous research on Calder's oeuvre. Is there any specific fact that fascinates you most?

Through my research I realised the ways in which Alexander Calder was constantly inventing new art forms out of the everyday. He was an extraordinary creator, constantly devising new concepts and coming up with new ideas. However, the most fascinating realisation was that Calder’s achievements were so radical that a whole new language had to be invented to describe his work. He is widely known for his mobiles and stabiles, two terms given by Marcel Duchamp and Jean Arp respectively to describe his kinetic works the former and his monumental stationary sculptures the latter. In addition, Calder’s own vocabulary when talking about his practice contained terms that were not common in describing an art practice. Using words such as ‘amplitudes’, ‘spheres’, ‘nuclei’, or ‘arrangements of planes’, to give only a few examples, Calder expanded the vocabulary that was traditionally employed to describe sculptural form and artistic processes. It was incredible for me while researching to be so close to the thinking and ideas of this great artistic mind.

Untitled (maquette) (courtesy Tate Modern)